01. A Bodily Religion

Christianity is a religion of the body. For that reason, the COVID-19 pandemic presents Christians with an incredible tension to live: the very same bodies which are the foundation of our salvation now seem to have become a danger; physical contact spreads the virus, proximity has become peril. If our usual instinct in a time of crisis is to feed the poor and gather in worship, these activities now threaten the lives of those we love.

To have a body means to be dependent. We are constantly dependent on things outside of ourselves: food to nourish us, shelter to warm us, air to sustain us. Dependence and bodiliness are, we could say, two sides of the same coin. Everything from movement and action to our highest activities—love, friendship, fellowship, family—all of these require us to be with and depend on that which is beyond our control. Our body is not a hindrance to these beautiful realities, but in fact their very foundation.

When Jesus Christ incarnates, dies, and resurrects, he not only reminds us that the body is the foundation of our humanity, but he also reveals that it is through our bodies that we are redeemed. This is one of the many reasons Christians reenact the Last Supper: to be reminded that it is through Christ’s body and blood that we attain salvation. Our dependency is not our downfall but the very means of our elevation.

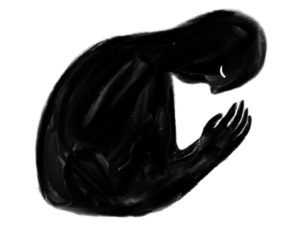

What happens, however, when this dependency is revealed also as a risk and a danger? That seems to be the situation the entire world experiences today with respect to the COVID-19 crisis. The very means by which we enact the greatest of human realities—the embrace of a good friend, the touch of a caregiver, the pleasure of a shared meal—have seemingly become a lethal weapon, which one wields unwillingly and unknowingly. Is this a sign that dependency, materiality, bodiliness, are not good after all?

The flesh is always the means of salvation,This is a paraphrase of the early Church father Tertullian’s way of describing the incarnation: caro cardo salutis, or “The flesh is the hinge of salvation.” The point is not that the flesh is glorified simply, but rather we transform and elevate our materiality not by running away from the flesh, but by facing the tension with which it presents us, as Jesus Christ does in the incarnation. but it has also always been true that the flesh poses a risk: the risk of temptation, the risk of vulnerability to what is outside oneself, the risk of sickness and ultimately death. This risk of the flesh has always been there, but that risk seems clearer now.

The Christian, I suspect, now feels this tension of the flesh in a particular way, precisely because his is a religion of the body, precisely because he knows salvation comes through Christ’s sacrifice of his own flesh and blood. This lack of others’ physical presence is even more acutely felt as we now find ourselves mediated evermore through disembodied technological means. As a Catholic, I feel the lack of the sacraments—particularly the Eucharist—in my life very profoundly. Even this I experience bodily: I feel their absence.

I am struck by the timing of this crisis: that it has come upon much of the world during the Lenten season, a time of lack, a time in which we remember our dependency (“Remember that you are dust and to dust you shall return”). I think often, especially as we approach Holy Week, of the time that the Body of Christ is taken from the tabernacle and not returned until Christ resurrects on Easter, of that night on which Christ is betrayed by his friend with a kiss, taken, scourged, and crucified, during which his disciples thought all was lost.

Perhaps we are being asked to enter into that night and day more deeply than ever before: what does it mean to be handed over to death by the embrace of a friend? What does it mean to think one’s friend is gone forever? That one will never embrace him again?

This crisis will likely last beyond Easter, beyond the moment the Eucharist will once again be placed in the tabernacle, beyond Christ’s return to his apostles in the resurrected body, at which point we will still be unable to celebrate the sacrifice together, to receive the sacraments, to be close to others. What then?

It was Mary Magdalene who was the first to see the resurrected Christ, and when she reaches to embrace him—the most natural movement in the world—she is told, “Do not touch me.” What must she have thought? Her Lord has returned, which she thought impossible, and he tells her not to touch him? I imagine it was then that the Magdalene experienced most profoundly this tension of the flesh: to see her Lord and move to embrace him and be told to wait and feel that lack of that embrace. Yet, I imagine that it was precisely in the waiting that she discovered her dependency on the Lord anew. She knew that she depended on the Lord and could recognize this all the more deeply in seeing him resurrected, and at the same time she was not yet given him completely.

We are a resurrection people, to be sure, but we too still live in the tension of the not-yet. This tension of the flesh reflects the not-yet of Christianity. And we find ourselves in a position to contemplate that more deeply than most of us have yet experienced. In these days of isolation and separation, I think it best not to forget the physicality of Christianity or try to push aside the tension we feel right now with regard to our own bodies, but rather to let ourselves lean into and feel the tension, and to the greater reality this tension points: our dependence on each other, and ultimately on the Lord. As we grow in our awareness of the lack—as we see the Lord but cannot touch Him—we can bring this felt lack into our prayer, as we suffer and experience the not-yet of Christianity in a profound way.

02. How to Practice Embodiment

What is needed are tangible actions to help us to live this tension, rather than running away from it:

- Writing letters. Phone and video calls may be easier, but they tend to present as one to one substitutions for being with friends and family in the flesh. The act of writing a letter recognizes one’s dependence on others and simultaneously acknowledges the pain of not being physically near to each other. A letter delivers a true aspect of oneself to one’s friend in a physical way, but also communicates the felt distance.

- Gardening, knitting, or some other kind of handiwork. These reflect the tension of embodiment in their deferral: it takes weeks or even months to see the fruits of our labor, and the matter at hand doesn’t always behave exactly as we’d like. But these simple tasks also bring us back to our bodiliness most profoundly—their simplicity reminds us of the great pleasure it is to be embodied, even in times such as these.

- Kneeling and prostrating during prayer. These physical acts remind us of the lack of the spaces in which we normally gather to kneel and pray. More importantly, however, kneeling and prostrating ourselves during prayer remind us, bodily creatures that we are, of our spiritual posture in front of God, and of our complete dependence on him.