In a short story, Jhumpa Lahiri writes about Mr. Kapasi, a man who translates to a city physician what rural Indian people say about their illnesses. When Mr. Kapasi complains to a friend, Mrs. Das, that the job is meaningless, she tells him that his occupation is a significant responsibility, that he is “interpreting people’s maladies.” Mr. Kapasi is greatly affected by her description. He feels named, enriched, emboldened, a person conveying delicate and dark truths.

For Mr. Kapasi, the words from Mrs. Das opened a window. He had perceived his work as a typical mindless job, but Mrs. Das offered a fresh perspective, a different and beautiful way to frame his work. She fulfilled Walker Percy’s rich phrase that one of the noblest roles of a communicator is “to render the unspeakable speakable,” to point to qualities others have been unable to articulate.

Most of us have had parents or coaches or teachers change our vision of ourselves by putting one of our characteristics into promising words, naming a previously unvoiced trait, making it “speakable.” We may have heard, “You are musically gifted” or “I’ve always seen you as a leader” or “I love the way you encourage your friends.” The expression of these words helped us see what was hidden.

It’s true for the words we use as well. Do I say my job is a necessity or a calling? Is America divided, polarized, or at war? Is God a loving friend or a distant relative? We often don’t see what we mean about things until we describe them. Every word is a window onto some vista.

So, if saying something reveals the insights we know, wouldn’t it also be true that struggling to describe something can show that we don’t quite know it? Sometimes students who receive a low grade on an exam exclaim, “But I know it! I just couldn’t access it in the moment.” Of course, that could be the case. Another explanation is that the feeling that we know something does not usually represent the same depth of knowing as being able to express it meaningfully to someone else. When we put appropriate words to things, we can learn more, others can learn more—and, in our most poetic and holy moments, we render the unspeakable speakable. We frame something so well it comes alive.

After years of emotional ups and downs, ecstatic peace and paralyzing anxieties, Angela asked to be admitted to the psych ward of the hospital. Through therapy and tears, she learned she was clinically depressed, a diagnosis that thoroughly liberated her. She said, “Because I could at times be so joyful, I never thought that my issue was depression—but everything fits together now.” She feels more clear-headed and stable than she has for a decade. “It sounds strange,” she says, “but I’m so grateful I can say ‘I am depressed.’ It’s the first step toward getting well.”

In Saying Is Believing, Amanda Hontz Drury makes a strong case that sometimes “we don’t know what we really think until we say it out loud. We often talk our way into our beliefs.” She doesn’t mean that we should try to convince ourselves of what we know isn’t true, but that beliefs—including our beliefs about God—move from fuzzy hunches to sharper conclusions when worked on by words. Speaking helps us to see the strengths and weaknesses of our beliefs and moves us from vague thoughts to concrete formulations, from “anxiety issues” to “clinical depression.”

All of this may sound logical, helpful, even inspiring. Who doesn’t want to say well what needs to be said? And it’s simple, right? Just make better choices with words. Yet even if we are gifted at doing so, the activity of framing is, as we have all experienced, far more complicated.

For one thing, we don’t begin with a blank slate.

01. We’ve Already Been Framed

Be safe.

Treat others as you want to be treated.

You can do whatever you set your mind to.

Don’t leave your towel on the floor.

Most of us heard these familiar lines as we grew up. We’ve had our lives framed for us by voices we could not control—and we’ve framed our own lives by our own choices, some thoughtful, some not. Sometimes it feels like a crime drama, like we are trapped by evidence that was planted. “It’s not my fault, officer! I live in the morally bankrupt twenty-first century!” We can even feel falsely accused, framed by someone out to get us, or by culture or history. When someone from a different culture calls me “an arrogant American,” I feel framed by the stereotype. When I find myself parroting some spurious cliché about “needing to stay young” or “how poor I am,” I feel framed by consumerism and advertising.

Perhaps we could all learn to be better detectives about the mysteries of what we say. Good detection begins with good questions. Two might be “What frames us that is not in our control?” and “What frames us that is in our control?”

Frames We Did Not Choose

What lenses have we inherited? Consider these categories. Heredity: I could say that my mom and dad gave me certain genes (white, male, “high-strung”). I frame the world the way I do in part because of my physical abilities, height, metabolism, and DNA-driven predispositions. Being the shortest, skinniest kid in every elementary grade influenced how I saw and talked about the world. Family upbringing: Since my parents raised me, they encouraged me to see the world in certain ways (do things right the first time, live and let live, be a man, etc.). National culture: Growing up in the United States, I learned particular values. Individual freedom is king. We’re the best nation in the world. I need to be constantly entertained. Social class: As part of the suburban middle class, I accepted the importance of education, hard work, and thrift. I felt safe. I learned prejudices against those unlike me: poorer city dwellers, country “hicks,” and rich “snobs.” Media: From rock music and television, I was told that romance and sex were the highest goods, that if indecision struck, I should “follow my heart” . . . or just go out and buy something . . . on sale. And these examples just begin to tell the story of frames that affected me.

Being a detective of our own influences is tough work, because we don’t usually notice our assumptions until we meet someone who doesn’t share them. Perhaps cousins from the city come to visit. An immigrant asks about American ways. We go to Thailand and meet locals who seem happier than most of our friends.

Frames We Did Choose

Another investigative question is, “What frames us that is in our control, that we have chosen?” Samantha was a good girl. She obeyed the Girl Scout law, rooted for underdog Olympians, competed for good grades, and watched her weight. She really watched it. As she looked at magazines and talked with her friends, she decided to accept their definition of “fat”—so she kept working on staying skinny. Though she lived in a beauty-conscious culture, she did more than inherit its labels. She decided which ones to make her own. Food equaled calories. Control meant slimmer thighs. “Slender” was not good enough. She chose these frames.

Of course, no matter how skillful we are as detectives, we can’t account for all the reasons we frame the world the way we do, nor can we reframe everything that comes into our awareness. We’d go crazy if we constantly evaluated every observation we made.

Wait. Why did I say “crazy”? How does that frame the event? Do I think people are going mad? Do I have a disorder? Am I being hurtful toward the mentally impaired—I mean, the brain-injured? You see what I mean.

If we constantly thought about how we were seeing things, we might never communicate at all—which is, after all, the point of speaking. If I read cookbooks all day long but never ate a meal, I’d starve. At the same time, if I never looked at recipes, my food might end up a mishmash of microwaved slop—which is how some conversations come out. So, it’s worth our time to examine the words we use to explain our lives.

Since we’ve all been framed, we are never a tabula rasa, a blank slate. We are embedded in what we inherit and what we choose. Though each word, each phrase, is but a pixel in the image of the world before us, a small part of the whole, we’ve all framed and reframed in ways that show the difference words make in our experience. Here’s why.

02. We Live inside the Frame

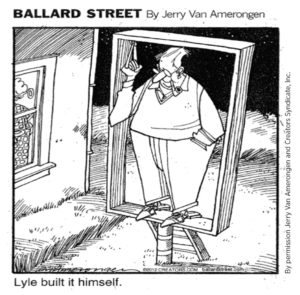

This comic from “Ballard Street” could not be more on target.

It seems silly for Lyle to have made a wooden box and stepped into it, a typical example of cartoonist Jerry Van Amerongen’s off-center humor. But, in fact, we all live inside the ways we have been framed and the ways we frame things. We see the world through the windows of our house. What else could we do? How else could we see beyond the walls that separate us from the world?

Consider Mark. When he went to work one morning as an intern in the Capitol in Washington, DC, he slipped by the tourists and went to his office. But not long after he arrived, he was running full speed out of the building, along with everyone else. It was September 11, 2001. Once the announcement came that commercial planes had crashed into the Twin Towers in New York City—and that another attack was on its way to DC—Mark took off. “The weirdest thing,” he said, “was that all I could think was ‘I’m in a movie.’ There I was running down the steps of the Capitol, out onto the lawn, my life in serious danger (or so I thought), and it’s like I’m outside of myself watching myself as an action hero in a film.” Like many in our media-saturated times, Mark imagines himself as an actor in a drama, focusing on his performance through the camera’s lens. He has his movie frame and he lives in it.

We Don’t Merely Stand Outside Words and “Pick Them Up”

This idea that we live inside our frames, our word choice, can seem counterintuitive. Aren’t words just tools we use and put down when we are done with them, like a hammer or a wrench? Take the word “mother.” We can’t use the word neutrally, like some dictionary word without any context. If your mother was kind and generous but controlling, your “mother” has these associations. So, when someone says “mother,” your memory of your mother is triggered, however slightly. The word also comes to you with the ways others have talked about their mothers—and a smattering of fictional versions of mothers. You can’t use the word “mother” as an unbiased term. It comes with your entire history associated with the word.

For these reasons, some people have problems using certain familial terms for spiritual relationships (father, mother, brother, sister, and so on.). If your father had an affair and ran out on the family when you were twelve, can you picture a Father-God who cares for you unconditionally? If your sister tormented you relentlessly, might you struggle to reframe yourself as a happy member of “the family of God”? These kinds of situations sometimes motivate us to work to reframe. We say we are trying to “redeem” a certain word or to recover its original, more positive senses.

We could also say that some aspects of our lives consist almost entirely of words—and part of our existence is lived in these aspects. What is our reputation but the words others say about us? Our reputation can change in a second if “word gets around” that we have lied or won a prestigious award. Isn’t our identity largely what we say (to others and ourselves) about who we are? If I talk about myself as an active, athletic person, who am I when I get injured? Most of us know retirees who have had difficulty making the transition from the work world, in part because their former labels don’t fit anymore. “I used to be important,” some say.

Here’s an example that reinforces the idea that words aren’t just tools. When I was in elementary school, textbooks emphasized the story of Manifest Destiny, of a U.S. sense of purpose in settling the West. Immigrants sacrificed everything for their children. Pioneers bravely fought Indians and built rugged homes on the prairie. I pictured this “sprint” to the Pacific Ocean as a glorious and inevitable victory for my ancestors, even though no one in my lineage ever hitched up to a wagon train. I lived in this view. It affirmed American values of risk-taking and hard work—and superiority to all who oppose true Americans.

Then, in college, I read a few books about this time period told from a Native American perspective: Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee and Custer Died for Your Sins. Wow. Massacres, broken treaties, relegation to desolate reservations. I realized how one-sided my education had been. It wasn’t entirely inaccurate, but I needed to reframe. I was living as an American in an image of our history that was limited, prejudiced, and reinforcing to my sense of special privilege. And this is also true: when I made adjustments to my view by changing my language, I stepped inside those frames too. Though we can increase our awareness and do our best to name situations well, we never get completely outside the frames. We can only see what our window-frames, however clear and large, allow us to see.

From Inside the Frame, We See Our Image of the World

So far, I have focused largely on words, words that create images in our minds, as did the story about Mark on 9/11. We could say that we live not so much in the world as it is, but in our image of the world. Words don’t create worlds (we can leave that to God), but they do create visions and versions of worlds. We see ourselves in a particular time and place, with a particular identity, and family and culture. We conform our behavior to our image of the world, an image we might happen to call exciting or depressing, pleasant or disagreeable, perhaps something resembling a movie or a chess game. If I see America as “a safe and gloriously free place,” I might live with more confidence and pride. If I see America as “a violent and greedy place,” I might live with more fear and ambition.

Our words select certain parts of the landscape, and that’s the landscape we tend to see. Researchers Andrew Newberg and Mark Waldman explain that the brain doesn’t put thinking and believing in one area and what we’ve learned through the senses in another:

If you ruminate on imaginary fears or self-doubt, your brain presumes that there may be a real threat in the outside world. . . . So choose your words wisely because they become as real as the ground on which you stand.

Our framing provides considerable power to see reality in particular ways.

Although our choices are varied and rich, frames are not utterly flexible. We can’t talk the world into being whatever it is we desire. Everyone who looks at you with squinty eyes is not out to get you, nor is the “cute young thing” next door thinking about you with every dip into the swimming pool. We can’t frame things any way we want—especially when there is too much evidence to the contrary. Or to put it another way, we can frame things any way we want—but if our labeling doesn’t sufficiently mesh with the world around us, we might end up in a mental institution. If you insist on saying you are Napoleon, I can’t stop you from doing so, but I’m quite glad that you aren’t actually a military megalomaniac.

Even so, within the boundaries of that evidence, we have considerable “naming” room. We can call the day a “successful turning point” or a “tragic step toward destruction.” We can say that our twisted ankle is a “catastrophic accident” about which we are “bitter” or a “forced Sabbath” for which we are “grateful.” We live inside our images of the way life works. And we are invited by God to do so.

03. We Are Called to Reframe

During my first few months away from home, I wrote my parents a “college is hell” letter. My roommate chewed tobacco and had a hangover every weekend, a bodily response that is considerably less pleasant in person than it appears in the movies. I was too much of a “longhair” for the conservative cowboy crowd and too much of a moral conservative for the Revolutionary Communist Youth Brigade. I didn’t seem to fit anywhere, not with the churchgoers or the nerds or the beer-guzzlers. I was lonely and alienated.

One afternoon, when reading through the New Testament for the first time in my life, I dropped my Bible onto the dorm room bed. I had just read, “In this world you will have trouble. But take heart. I have overcome the world” (John 16:33). I was stunned by the drama of these words. Suddenly, in my epiphany, the world changed from “a place of trouble” to “a place where Jesus has overcome the trouble.”

Biblical Scripture constantly reframes things and challenges its readers to do the same. The world is not random; it’s created. It’s not just murder that’s a problem, it’s anger. Your good works and religion don’t suffice; you need redemption. On one level, all scriptural assertions say, “It’s not THAT (randomness, murder, works), it’s THIS (Creation, anger, redemption). Don’t talk about your faith like THAT, in spirit-killing legal terms. Talk about it like THIS, in life-enhancing terms of grace.”

In fact, every conversation is an invitation to reframe, a request to see things from a slightly to significantly different point of view. Bob says, “I don’t think the movie was insightful” (THAT). “It was sentimental and dull” (THIS). Or “Life isn’t hopeless; it’s purposeful.” Requests to reframe are not intrusive, objectionable acts. They are unavoidable if you plan to have any contact at any hour with any human being. We are constantly calling others to reframe, and listening to the reframing of others. Reframing is central to human existence—and so it is central in all discourse, including Scripture.

In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus highlights the importance of framing: “Anyone who says to a brother or sister, ‘Raca’ [you are contemptible], is answerable to the court. And anyone who says, ‘You fool!’ will be in danger of the fire of hell” (Matt. 5:22b). And when speaking to the Pharisees later on, he says, “I tell you that everyone will have to give account on the day of judgment for every empty word they have spoken. For by your words you will be acquitted, and by your words you will be condemned” (Matt. 12:36–37). I’m taken aback every time I read these passages. All those careless, hurtful, angry words I’ve used! In our language-lazy times, these are fearsome words about words. As Eugene Peterson says, “For those . . . who decide to follow Jesus, it only follows that we will not only listen to what he says and attend to what he does, but also learn to use language the way he uses it.”

Though Jesus doesn’t mean that our words are all that matters, he does mean that our words matter. The byword of our day, “whatever,” as in “who cares,” does not reflect an appreciation for language. I see this language-attentiveness in Jesus’ disciple Paul. In the book of Romans, he asks, “What shall we say?” (italics mine) seven times. In each instance, he implies, “Should we continue telling ourselves error? No, we should speak the truth. We should live the truth.” Romans 6:1 says, “What shall we say, then? Shall we go on sinning so that grace may increase?” Certainly, Paul doesn’t want us merely to say, “We have decided to stop sinning.” He wants us to stop making life-crushing choices—but he also wants us to stop justifying them by the way we frame them. We are more likely to sin if we give sin our verbal blessing.

Since every word is a window, we are all called to examine our speech, our conversation and writing, to ask whether the view out a particular window is worth our gaze, whether our THAT should actually be a THIS.

***

Years ago, astronomer Johannes Kepler inspired scientific work by calling it “thinking God’s thoughts after him,” encouraging researchers to follow the logic of God’s mind. Perhaps the inspired goal of good framing is “speaking God’s words after him,” encouraging communicators to pattern their language decisions after God’s choices. Both can lead to restoration or reformation, even resurrection.

04. For Reflection

Morning Tapestries

The fabric of this summer day unfolds

in loose bluebird threads and yellow

warbler weavings; it clothes the hill

above my sandstone wall in browned

grass stitches; it blends down and

blurs up into a madras of acorns

and oak leaves and dappled sun. What

a miracle to hold the hem

of God’s garment, his earthly covering,

to slip into this billowing, blousy praise.